Terraform vs Bicep: the differences you should really know

What really matters if you work with Azure and need to choose between Terraform and Bicep

This post has been updated in late October 2024 with the public preview of Bicep extensibility feature

For a few years now my professional coding time has been dedicated to writing Infrastructure-as-Code and CI/CD pipelines for several customers working with Azure. I now have some real-world experience in both Terraform and Bicep and as I have read several posts comparing the two, I want to share my opinion on this.

If there is one thing to keep from this post it would be this: this is a not a mono or multi cloud issue, you have to think beyond that. To elaborate on this, I will focus on two differences that are not talked about enough.

I have started to work on this article before Terraform licence’s change and the rise of OpenTofu (yes, I needed time for this one), so everything written here about Terraform applies to OpenTofu as well.

First difference: the execution mode

One of the most important thing to understand is what is happening on the machine executing Terraform or Bicep (note that the machine could be your workstation or a CI/CD runner).

Using Bicep

When you give a file to Bicep, it will find the dependant Bicep files, “compile” the whole thing as an ARM template and submit a deployment in a single API call to Azure. From there all the work is done within Azure, the caller (your workstation or CI/CD runner) monitors the status of the deployment and waits for its completion.

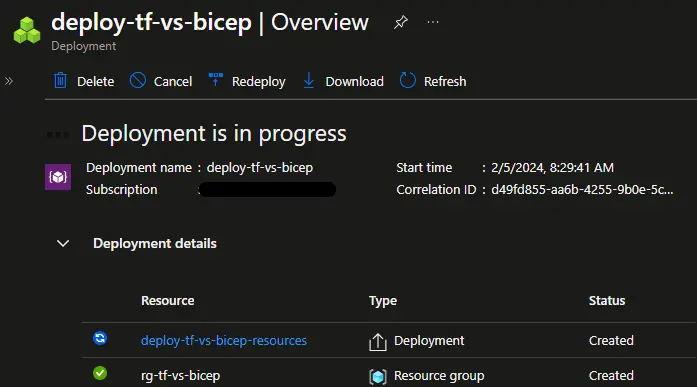

As the deployment is made by Azure, pretty much nothing happens on your machine You can also monitor the execution and see the result from the Azure portal in the deployment blade of the targeted management group, subscription or resource group:

As the deployment is made by Azure, pretty much nothing happens on your machine You can also monitor the execution and see the result from the Azure portal in the deployment blade of the targeted management group, subscription or resource group:  Viewing this in the portal will not happen if you use Terraform

Viewing this in the portal will not happen if you use Terraform

Using Terraform

When you run terraform plan from a folder, it compares the whole configuration (the *.tf files) with the state to determine the changes to make on the resources in Azure. Then running terraform apply will make the changes on the resources and reflect them in the state.

For both commands there is no deployment submitted to Azure, but a lot of calls to the management API are made to create/read/update/delete the resources in Azure. The order of the API calls is determined by the logic of Terraform and its providers, this logic is executed on the machine running the Terraform CLI (your workstation or CI/CD runner).

Once the configuration has been applied you won’t see any deployment in the Azure portal, as the AzureRM provider of Terraform doesn’t use them. Instead you can see a bunch of entries in the Activity log of the affected resources.

When using Terraform, a lot of calls are made from your machine

When using Terraform, a lot of calls are made from your machine

What does it change ?

Once this explained, let’s dig in what this difference changes with several examples.

The ability to interact with other tools, APIs, or clouds

First, Bicep’s execution mode limits its capability to interact with other things: as the whole deployment is done remotely you can’t for instance insert a delay between two resources. You can’t either interact with another API, or another cloud.

In fact, as Bicep compiles into an ARM template, it is de-facto limited to what ARM templates can do, which is what the Azure Resource Manager API can do. So you can do anything as long as it’s related to an Azure resource, which excludes:

- Uploading a blob to a storage account (a blob is a data, not a resource)

-

Interact with Azure AD/Entra ID:You can’t activate Easy Auth on an App Service as you’ll need to create an App RegistrationYou can’t get existing AAD objects like groups from their names to assign roles (you have to provide ids)

Update: Interacting with Entra ID in now possible in public preview with the extensibility feature and the MS Graph provider for Bicep. I have made a post about this feature 😉

You can still work around these limitations either by:

- Using Azure CLI and providing input values to the Bicep deployment

- Using deployments scripts, which means uploading a script to a storage account, and spin a container instance to run it. Kinda overkill in my opinion, and something you should avoid if possible, just like Terraform’s provisioners.

Code organization

Another thing to notice is how each tool gets the code to apply. Bicep requires a file as the deployment entry point, and will treat all called .bicep files as nested templates. Terraform doesn’t need a starting file, it will read all *.tf files in the current directory and find called modules from there (the name main.tf as the root module is a naming convention, not a constraint).

Basically Terraform doesn’t care very much how your code is organized: within a module (including the root module) you can split your code into several .tf files as you wish.

On the other hand, Bicep considers each .bicep file (except the entry point) as a module. So if you want to split a file for readability reasons, you have to break it into several modules (maybe for the better if that file is too long).

The need to determine values at the start of deployment

Lastly, as Bicep compiles everything in a single ARM template and sends it to Azure, this single template has to be predictable.

This implies limits on looping, for instance as stated here in the documentation: “Bicep loops only work with values that can be determined at the start of deployment.”. It is also not possible to iterate on a module or resource collection (an index must be applied here).

Another aspect of this relates to file management: for all file functions, the filePath parameter can’t include variables. This is because Bicep reads the whole file and put the content in a string in the generated ARM template. This happens at compilation time and can’t be done once the template has been sent to Azure.

Once again, nothing very limiting here, only things that can be worked around, but good to know to understand how each tool work. Let’s move on to the second difference.

Second difference: state vs no state

The state is a key-concept specific to Terraform. Basically it’s an abstract layer used to map real world resources to the configuration. It’s something you might dislike at first for the following reasons:

- As it contains a representation of you infrastructure, including sensitive data, it’s something that you need to secure. Whether you put it in a storage account, use Terraform Cloud or another backend, this is an important governance choice to make, and it can be complicated depending on you organization

- If a change is made without Terraform on a resource previously created with Terraform, it will introduce a drift, aka a difference between the state and the real world infrastructure. This can be made by humans using the portal, but also by Azure itself: for instance when a managed certificated is automatically renewed by Azure, the new thumbprint is not updated in Terraform’s state.

Depending on the situation it can be trivial or tricky to address, but you should be prepared as it will very likely happen.

Of course Bicep can’t have drift problems

Of course Bicep can’t have drift problems

But once familiar with the state you’ll become confident in dealing these and you’ll appreciate the features it brings. Of course in Bicep, there is no state, we can say that the infrastructure is the sate, which is simpler to handle at first but you will see in the rest of this post the features you might miss.

The state is not an easy topic, to better understand it I recommend reading this page from the official documentation and also this one who explains why it is required

What does it change ?

Let’s add some details on what the state brings in terms of features and potential problems.

Destroying resources

First, the state tracks resources created with Terraform. So if you remove an already created resources from your configuration (your code), and run terraform apply again, the resource will be removed from your infrastructure as well.

With Bicep, assuming you’re using the default incremental deployment mode, the same test will not remove the resource from the infrastructure, as Bicep don’t know if it has created the resource or not.

Generally, Bicep/ARM will never attempt to delete a resource, whereas Terraform will consider that changing certain properties (like the name or location) will force the resource to be deleted and created again.

Ease of refactoring

A consequence of the previous point is what can happen when you refactor your code.

For instance in your Terraform code if you change this:

1

2

3

resource "azurerm_resource_group" "rg" {

name = "rg-my-resources"

}

To that:

1

2

3

resource "azurerm_resource_group" "rg_renamed" {

name = "rg-my-resources"

}

The resource group rg-my-resources will be deleted and re-created during the next apply, even if the name in Azure doesn’t change. Same thing will happen if you move a resource from a module to another.

To prevent this to happen you the best way is to use the moved block.

Refactoring Bicep code is simpler, the same kind of action will not impact your Azure resources.

Behavior regarding outside changes

Generally Bicep is more tolerant to changes made by other actors. By actors I mean humans using the portal or other services working in the background.

Let’s take the example of App Service certificates again: whether they are managed or retrieved from a Key Vault, they are retrieved by a service principal associated to App Service in your tenant, automatically in the background. And as the Terraform state and the resource associated to the certificate contains the thumbprint, the next apply after a renewal can remove and try to re-create the certificate with the previous thumbprint (trust me, I have already broken production like this 😭).

This cannot happen using Bicep as it doesn’t track those kind of information in its state (as it doesn’t have one).

Storing non-resources stuff

Another feature the state brings is the ability to store resources that don’t exist in the infrastructure. For instance the random provider generates random values (GUIDs, passwords, pet names, etc.). Each value is stored as a resource in the state, so the values are re-used by the upcoming runs until the resources are destroyed.

Bicep handles randomness in a different but clever way: the uniqueString function generates a deterministic hash depending on the provided parameters. I always use it with at least my subscriptionId in my open-source repos, so anybody can use my code in their subscription and will get a different and unique value.

Keep in mind that the randomness behavior is different for each tool: Terraform will generate a new value every time the random resources is created, but Bicep will always generate the same value unless the parameters change.

Other minor differences

There are less important differences between that should not been considering when choosing one the other, but still are worth mentioning.

Language features

As Terraform is older that Bicep (created in 2014 vs 2020), and is less limited by its execution mode, it naturally comes with more features: more built-in functions, more looping capabilities, a console command to experiment in your terminal, etc.

But Bicep is steadily catching up, and some of the latest features greatly improve the coding experience, for instance user-defined types, null-forgiving and safe-dereference operators, or user-defined functions.

VS Code integration

I have been using Visual Studio Code as my main IDE for many years now, and I use the following extensions for Bicep and Terraform code:

- The official Bicep extension by Microsoft

- The pre-release version of the Terraform extension by HashiCorp

At the time of writing this post, I definitively prefer the experience brought by the Bicep extension. Overall, writing Bicep code is very nice: the intellisense is blazing fast, always relevant, it never gets in the way of my “flow”, it just works flawlessly. And renaming elements is supported !

I really hope the Terraform extension will reach this level as currently I feel that I need to manually trigger a snippet to get some intellisense, and it often feels like it show a list of keywords without considering the context.

Also, it’s a personal preference but as both syntax are similar, and Bicep’s is strongly inspired by Terraform’s, I find Bicep’s syntax easier to read, more elegant and minimalistic.

Tooling

The wide use and open-source (initially at least 😏) nature of Terraform have made the community build many tools over the years: Checkov or Terrascan for compliance, terraform-docs for generating module documentation, Infracost for FinOps, and even Carbonifer to estimate the carbon footprint of your changes !

As Bicep is Azure-only, less tools have been built around its usage. I have already used Template Analyzer who works for ARM templates and Bicep files. Also Bicep comes with a built-in linter who checks for best practices and coding standard violations at compile time and while editing in VS Code.

Support of new Azure services or features at launch

This is something that comes often when comparing Terraform and Bicep:

If you want first day support for new services and features, you better have to use Bicep over Terraform.

This make sense as Bicep calls directly the ARM API, and Terraform requires its azurerm provider to be updated accordingly. The best example of this is Azure Container Apps, their support in the Terraform provider took months after the service went GA (General Availability).

This statement was surely true a few years ago, now it’s much less obvious as a new service has to be supported in the Terraform azurerm provider to be GA in Azure (it has been announced at Build 2023 in this session).

Also the AzApi provider is a good alternative for services not already supported by the provider, much better than using provisioners. So even if you need to use a feature that is not supported by the provider yet, you should be able to work around that quite easily before proper support is added.

I also like to bring a counter-example to this statement: the static website feature of storage accounts. It’s not a new feature at all, but it’s still not supported by ARM templates, thus not by Bicep. You have to use Azure CLI to enable or disable it, this means using a deployment script in Bicep.

The azurerm Terraform providers works around that limitation so that this feature is natively supported.

GitHub repository !

Speaking about static websites in Azure storage accounts, I have prepared this repository that shows how to create one both in Bicep and Terraform.

Initially it was for a talk on this very same topic, you can check it out, compare both usage and mess up with the code !

Wrapping up

Let’s finish this long article by making a choice between the two. Personally, at the time of writing this, Terraform is my go-to IaC solution. I have seen comments stating that Terraform has won the “IaC war”, and I guess it’s true for now: the integration with many tools and a the ability to destroy resources removed from the code are hard to beat.

I also think that Bicep strongly deserves more than a look. From what I have also seen in the Bicep’s repo, the people building it are brilliant, and I’m quite amazed on how they achieve to make the language evolve, considering it’s built on ARM template foundations.

I guess they believe in what they do and have good reasons to do so: it’s a well designed language and big upcoming features could become game changers: deployment stacks for resource lifecycle, and extensibility is also in public preview (check the docs and my post for MS Graph and this page for Kubernetes).

For some use-cases I’ll choose Bicep over Terraform, for instance small projects/customers (especially if no one will do IaC when I’ll leave) or chicken and eggs problems (like provisioning the storage account holding Terraform’s state).

For the rest, I’ll stick with Terraform as it keeps people from using the portal too much and generally, it scales better… for now 😏